Complex Simplicity

When the Going Gets Tough: Challenges in the Face of Adversity

Building a substation in the middle of Mozambique was never going to be easy, but building a substation in a remote area, during rainy season and in the midst of COVID pandemic was quite a feat.

In 2018, Kenmare, one of the world's largest mineral sands and titanium producers, made a decision to expand its Moma Mine operation to the Pilivili site, approximately 20 km away. It was a gargantuan undertaking, requiring an investment of over US$100 million to build the required infrastructure and to move a 7000t plant and a 1700t floating dredge to the new location.

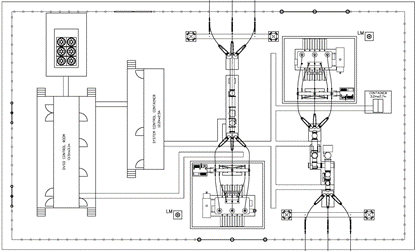

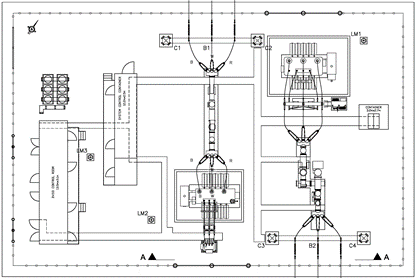

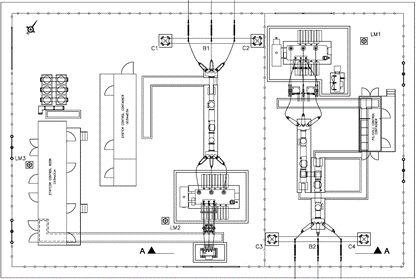

MATREX had the rare privilege to be among the companies that were involved from the conception of the Project to its completion. Our role as Engineering Consultants was to provide engineering solution to compensate the Moma Mine 110 kV system by installing a 110 kV STATCOM at the new Moma B Substation and to provide the power to Pilivili via a new 110/22 kV substation Our deliverables included detailed technical specifications, evaluation of the tender, detailed primary, secondary, civil and structural design, witness FAT and SAT and perform inspections during construction.

The Mine itself is on the coast of the Indian Ocean, in a remote area of Nampula Province, over 2000 km from Maputo, the capital city of Mozambique. The roads are almost non existent and the few existing access routes need extensive maintenance on annual basis due to torrential rain.

The design faced three immediate challenges. The substation had to be built close to the sea and within the mine itself. That meant that the equipment would be exposed to heavy industrial pollution, tropical rain and salty moisture from the sea. The space was limited and the design had to provide a solution that would fit within already built infrastructure.

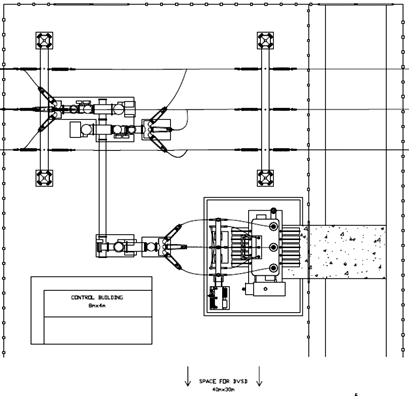

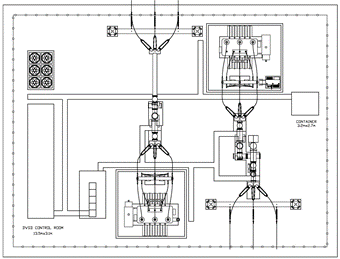

These initial challenges were addressed during the feasibility study. Highly Integrated Switchgear (HIS) was chosen for the 110 kV voltage level, as it requires minimum substation footprint and is inherently resistant to the effects of the highly corrosive environment. Its short delivery time and simplicity of installation was beneficial for the project’s very tight implementation schedule.

While the tender documents were developed, the lack of space required us to come up with an unorthodox solution and propose to feed the Pilivili Substation from transformer and OHL bays that would be collocated in the same area as Moma’s STATCOM. These bays were to be fed from two different power networks, have separate MV switchgear and protection and they would supply power to two different users. Traditionally, they would be positioned on two separate sites.

The tender drawings reflected the layout of the entire Moma B site, but the Moma’s system compensation and the Pilivili’s power supply, due to financing issues, had to be managed as two completely separate projects. Initially, two tenders were issued, with the scope of work being split between the two substations on two sites and the connecting overhead lines.

In the middle of the tendering process for Pilivili SS, Covid-19 raised its head, and the Project had to fit within what was available to purchase and to utilise the skills already available in the country. Consequently, the project had to be divided into a number of smaller tenders. The equipment and materials were sourced separately and issued to various contractors. FAT, SAT and site inspections were done remotely and the manufacturers had to provide remote support during installation.

This required all documentation, specifications and drawings to be issued for a specific contractor and often, the design had to be adjusted to accommodate what was available on the market. Some equipment had to be altered and some materials could not be sourced and that had to be reflected in the design. The Project implementation schedule was suffering and many delivery dates became a moving target. The design had to be adapted to allow two contractors to work simultaneously on site and for each bay to be energized independently.

Never, in over 20 years in the history of our company, did we come across a project that was so simple in design and so complex in management and execution. MATREX had to not only provide the said design and specifications, but to also provide an end to end engineering solution that would ensure a viable implementation of the project in its entirety.

The Project was in full swing exactly at the same time as the pandemic was gripping the planet. Of course, problems kept creeping in and had to be addressed on daily basis. Some corners had to be cut and some things were missed, because not all required engineers could be on site to physically inspect everything. Any problems were quickly fixed with clever design and full-hearted support from competent construction and installation contractors. Honestly, there were even less problems than encountered on a typical project, since everything was well planned, double checked and closely managed.

On few occasions, we truly felt like Houston at our own Apollo mission – not a big problem in normal circumstances, but quite a big deal during a raging pandemic and worldwide lockdown.

Just to illustrate it, there was a crisis to the correct yard stone. Due to the high soil resistivity, the yard stone had to have a certain high resistivity value. Typically, it would have been easy to source it from South Africa, but the border was closed. The local quarry was working, but it never tested its stone. There was an engineer in South Africa who could test it, but he had no equipment to do it. So a team of 15 people, chatting via email, organised in one day for someone to pick up the samples, drive them to Nampula, get it to South Africa and test it. We got the test results within a month.

That’s long, you say. But the team had to organise an international charter flight, get the special equipment from overseas, clear a myriad of customs and get a volunteer to sit 14 days in quarantine. All this during lockdown! Oh, and the test procedure takes a week to complete! Best news, we could use the yard stone from local quarry.

And yet, after all that, the commissioning engineer, who had endured a small odyssey to be our representative on site, proudly informed us that, when the time came to energize the substation – he just pressed the button and it worked!